Hello fiber lovers! We have all wondered what is the warmest yarn to spin and knit. If you ask the internet what is the warmest natural fiber the consensus says Qiviut. While researching this, I couldn’t find a site that explains how this was tested so I decided to test it myself. I went into this expecting to see Qiviut was the warmest fiber and I just wanted to see by how much was it the warmest. My testing results were shocking!

I also made a video covering this topic. If you prefer the video format you can see it here.

Results

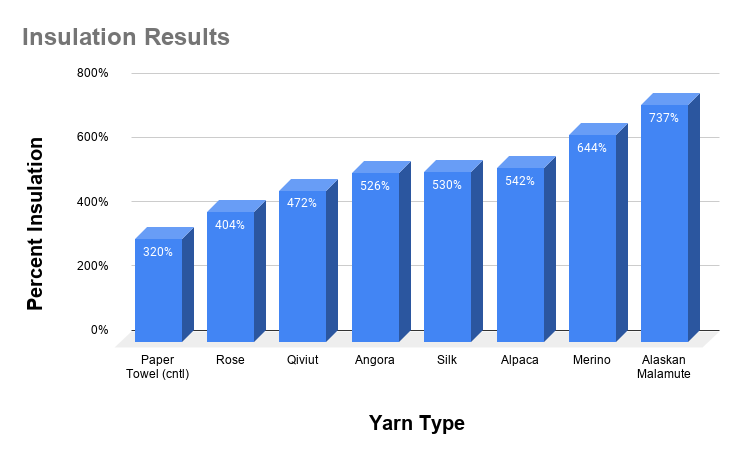

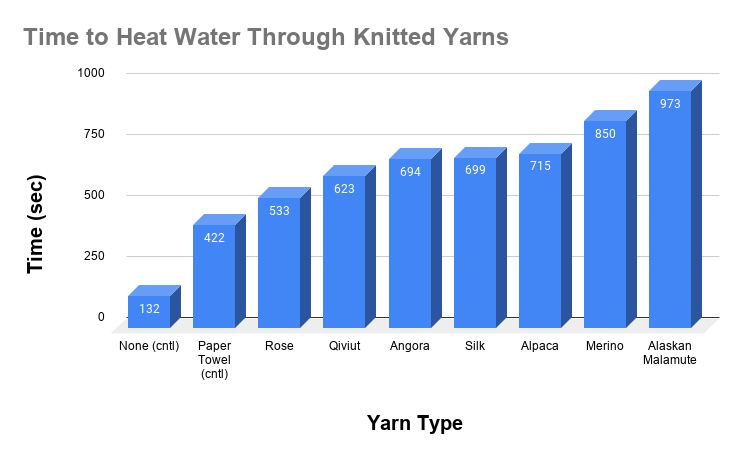

I’m not one to build suspense so the results are directly below. These results show how well different knitted test swatches insulate compared to no insulation. The testing methods section at the end of this post goes into the full details of how the testing was done.

These are not the results I was expecting. I collected results multiple times just to make sure the results were consistent and they were. All the test swatches are as close to the same density and thickness as I could get. I did some measurements on the thickness and they are all between 4 and 4.7mm. Even if I adjust for the slight difference in thickness it doesn’t make a difference in the rankings here.

From my testing this is how I’d rank these different yarns from warmest to coolest.

- Alaskan Malamute

- Merino

- Alpaca

- Silk

- Angora

- Qiviut

- Rose

Paper Towel (Control)

This was included to give a control to compare against. Obviously a single sheet of paper towel isn’t a great insulator, but it is significantly better than not having any insulator. It took 3.2 times as long to heat through a paper towel than it took to heat the water with no insulator between the hot plate and the water.

Alaskan Malamute

The Alaskan Malamute is a dog that was bred to haul heavy freight as a sled dog. So it should be no surprise that the their hair when turned into yarn is extremely warm. It was my warmest sample I tested by a significant margin. The yarn only uses the dog’s soft undercoat so in addition to being very warm it is extremely soft. The sample was probably the softest of any of the samples I had and it had a beautiful halo.

The problem with this sample is this isn’t a common type of fiber which makes it hard to get and really expensive. The good news is the next warmest fiber on my list is much easier to get so let’s look at that one.

Merino

This is the type of wool people say to use when you want a warm sweater, and it didn’t disappoint. It suprised me that it was the second warmest yarn in my tests. I expected some of the other exotic yarns to do much better, but after rerunning the tests several times I’m convinced in my testing with my samples it is the second warmest yarn. An added bonus is this is a fairly easy to get yarn and less expensive than most of the other yarns on this list.

Alpaca

Alpaca’s performed well in this test. It turns out it isn’t quite as warm as Marino, but it did get third place in my testing. Alpaca’s are native to cold environments in the Andes Mountains and their fiber is an excellent insulator. I did some looking online to see how arm Alpaca is and it was certainly classified as a warm fiber. like that my testing shows how it compares to others.

Silk

I wasn’t sure how silk would perform with insulating since it is from a silk worm that uses the silk to form a cocoon to protect themselves during metamorphosis, where as wool is there to keep sheep warm. That said, silk did a good job in my tests. It took around 5 times as long for heat to permeate the silk test swatch as compared to having no isolator. Silk is also a light weight and soft fiber.

Angora

Angora fiber is the undercoat of Angora rabbits. When I searched for the warmest natural fibers it was usually Angora and Qiviut at the top of the list. So it was a shock that this fiber came in fifth place. To be fair the fibers that placed third through fifth were all very close so you could argue that Angora was basically tied for third. Still based on what I read online I was expecting this to do better than Merino wool, but it is well behind that. On the plus side this fiber was extremely soft and had a great halo.

Qiviut

The internet says this fiber from a musk-ox is warmest fiber. Many places say it is eight times warmer than wool. This is where my testing completely disagrees with those statements. I found Qiviut was not even close to as warm as Merino wool or a bunch of other fibers. The sample I purchase, which is the most expensive yarn I’ve ever purchased by the ounce, was from what seems like a reputable Qiviut fiber dealer and it was very soft.

I’m still a bit in shock that that Qiviut tested so poorly in my testing. I have verified my test swatch is similar in thickness to my other samples. I would like to test another sample of Qiviut someday, but I just can’t justify that expense for this blog post right now. That said even if I find a sample that is much warmer, it would still be difficult to beat some of the other fibers tested here.

Rose

This knitted test swatch was the worst insulator of the knitted test swatches I tested. There are certainly times where you want a beautiful knitted garment, but you don’t want it to be too warm. Maybe it’s a warm summer night, but you want to wear that shawl on the beach. In those cases Rose yarn would be a good option.

This is fiber made from rose plants and turned into yarn. It is a cellulose fiber so I didn’t expect it to be a good insulating fiber. While I didn’t test it, bamboo would probably have similar properties and is more commonly found in yarn.

Update – There is some controversy about whether rose fiber is from rose bushes. Check out this article for another point of view.

Does Human Body Warm Impact These Results?

Testing how warm people perceive different fibers is a completely different test. I’m including this section because it’s going to be a common question and I want to try and address it.

The human body is constantly generating heat at some point the insulating properties of the clothing you are wearing keeps enough of the heat on your body comfortably warm. So while the percentages above can help you see the relative insulating properties of different fibers, you shouldn’t take these numbers to be how warm they keep you in all cases. The human body is constantly adapting and switching from warming to cooling states so there is fairly wide range of temperatures you can be comfortable. Because of that even though some fibers might be better insulators, you might not even notice a difference in many situations.

From talking with many spinners and knitters, I believe softness of a fiber likely impacts how warm people think a fiber is. The mind is powerful, and just as sugar pill placebos can help reduce certain ailments I’m pretty sure people’s perception of what a warm fiber is will help keep you a little warmer. This isn’t going to keep you warm in really harsh conditions, but if you are comparing two different sweaters on a cool fall evening perception your mindset could well make a difference. I don’t have any papers directly addressing this this type of behavior so feel free to treat this point with some skepticism if you require that kind of proof.

Some fibers keep you warmer when wet. This page does a good job of explaining why wool has this property. In certain conditions this effect will affect how warm clothing feels.

Thickness is going to matter. If you have two scarves made from the same type of yarn, but one is knitted so the scarf is thicker then it will feel warmer. Use this to your advantage by trying to knit thinner garments when you want them cooler and thicker garments when you want them warmer.

So taking all this into account if you really wanted to figure out what knitting clothing feels the warmest, a scientific way to do that would be to create simliar thinkness/gage mitten out of several different yarns. Then have a lot of people try it on and put their hand in a cold box. You shouldn’t let them see the mitten or know which one it is. Ideally you would even put some extra covering over their hand so they couldn’t feel the fiber so that perception had minimal impact on this test. Then ask them to rate the warmth of the different mittens on a scale of 1 to 10. While I’d be interested in this kind of test it was beyond the scope of this post.

Testing Methods

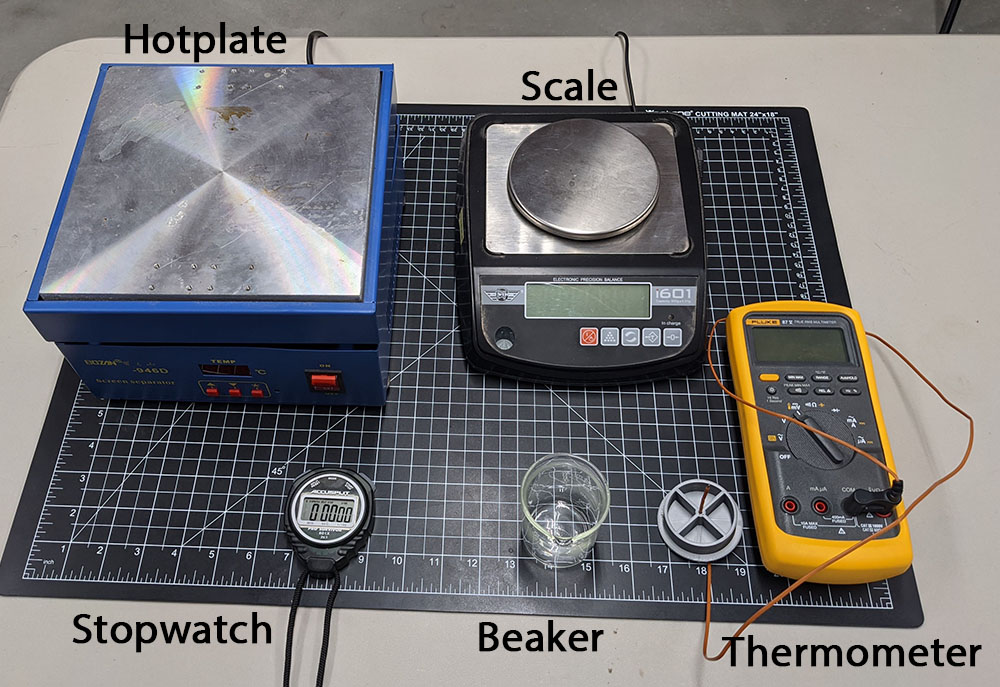

I want to explain how I am testing this for a few reasons. The first is I couldn’t find anyone explaining this and as I mentioned in the introduction it’s important. Another reason I’m explaining my testing method is because it isn’t a standard method. The best way to do this testing would be to use thermal conductivity meter, but these chambers seem to cost over $10K USD which is way beyond my budget. I am using a modified version of the guarded hot plate method which is one of the most commonly used methods for measuring the thermal conductivity of insulation materials. Chapter 2.1 in this document explains this method. My version is modified because I only cared about a the relative difference in the insulation properties and thus didn’t need the much more complex Poensgen apparatus described in this paper.

Here are the tools I use in my method:

- Thermometer (I’m using a Fluke DMM with a temperature probe)

- Scale (I use this to measure 50 grams of water)

- Stopwatch

- Hotplate (I’m using a solder reflow plate because it’s accurate and has a controllable temperature)

The basic procedure is I put 50 grams of room temperature water into a small beaker. Then I put the insulator (a knitted test swatch) on the hot plate set to 120 degrees Celsius. Then I put the beaker of water on the insulator and measure the time it takes to raise the water by 10 degrees Celsius while using a 3d printed cover for the beaker to hold the thermometer in a consistent position. The longer it takes to heat the water the better the knitted test swatch insulates the beaker from the hot plate.

The main issue with this test is I don’t have it calibrated to give an output of thermal conductivity in the standard units of watts per meter-kelvin. It would be nice to have that, but a system that does that is more complex and beyond the scope of this project. Instead my measurements are only useful to compare them again each other. My testing methods work because I want to find the warmest yarn and my test will tell me which of the yarns I’ve tested is the warmest relative to the other yarns.

I want to give a huge thanks to Kathryn, who goes by the the alias CraftMeHappy on Ravelry for donating many of these test swatches.

FYI. Qiviut is pronounced Kee Vee Ut.

Thanks!

When I saw the title of this article I thought, “Oh no, he is going to say that surprisingly acrylic is the warmest fiber.” Whew…so relieved.

I did want to measure acrylic just to compare. I don’t expect it to be very warm, but the results would be interesting. The problem is we couldn’t spin it ourselves and didn’t have a yarn that matched our other samples very well so it wouldn’t have been a fair comparison to include it.

You didn’t test Possum or Polar bear fur both hollow, or beaver or seal ,and walrus please research thanx

It is mostly limited by the samples I have. If you’d like to send me samples of those I’d be happy to test them.

Walrus don’t have enough hair to spin. They are “nearly naked”. 😉

These aren’t fibers that are in yarns, Mark. 🤦🏻♀️

Possum is used to make yarns, though I have only seen it blended with merino. Were you talking about single yarns? Anyway, I have some possum/ merino gloves from New Zeeland.

Thanks for doing this! I love seeing science applied to the fiber arts 🙂 One thing that I didn’t see addressed anywhere is how controlled the yarns were? Were they all spun with the same method at the same thickness? I’m not sure if this would be the right control, but I *think* maybe they should all be the same approx weight, yardage, and thickness, spun with the same method (trapping a similar amount of air). The amount of air trapped inside a yarn could definitely affect the insulation properties. Sadly, I’m not a consistent enough spinner to accomplish what I’m describing, or I’d whip up another set of rest swatches :/

I did my best to make all the samples as similar as possible. The things you mentioned were made similar, but I’m sure there is some variance. I would like to do directed tests for a lot of those things by just changing one thing at a time with the same fiber to see how much that changes the insulating properties of yarn. If we find that changing how you spin or knit the yarn has huge impacts on the warmth of a fiber that would be really interesting information too.

It’s “common knowledge” that the preparation of the fibers and style of spinning will affect the warmth of the end result (which is not to say it’s true, just that many have claimed it’s true). Combed vs carded fiber, woollen vs worsted spinning (although that’s a spectrum rather than bimodal). The densities of the fibers themselves matter – alpaca and angora are usually described as the warmest *per weight* because they are both hollow fibers and lighter than a similar volume of merino. Alpaca itself has 2 main types (huacaya and suri) with noticeably different qualities. And of course, the individual variations in the quality of each type of fibers would be difficult to take into account; not all merino are made equal and the term is applied to a very very wide variety of wool (what Aussies call “good merino” would barely qualify as merino at all under some standards).

Go malamutes! I happen to have one and I have spun some of his fiber. I am still trying to master removing the top coat hairs though, otherwise it makes for a slightly scratchy yarn. I really am not surprised by the result, though it turns out that dog fur is not x7 as warm as wool, and angora is not 5x as warm as wool, which is what I’ve read.

I want to do more testing to see if I can isolate what makes differences (maybe how the yarn is spun will matter a lot which would be interesting), but this very clearly shows that a lot of the numbers out there are either completely wrong or were came up with using some “interesting” tests. If anyone finds out where the existing numbers of 5x and 8x for Angora and Qivuit come from let me know.

Wonderful experiment! As others have noted, inconsistencies in how the yarn was spun, thickness of yarn, how tightly the swatch was knit, all affect the results.

I’m curious to know how well a given fiber keeps the water warm. I’ll try to explain. Let’s say you heat your 50g of water to temperature H, place the little beaker in a cozy, and track the rate at which the water cools off. I know this experiment would suffer from some similar downfalls as your original one with regards to the handmade nature of the swatches(cozies). One thing this second experiment removes from the equation is damage to the fibers from direct contact with the heat source. I don’t know how long it would take for these fibers to break down due to heat, or to what degree the direct contact with the heat source changes the fibers; I’m really just thinking out loud here.

Thanks! I am working on a new experiment that is similar but not exactly the same as what you described.

I can’t wait to see it and the results!

Maurice, you have a lot of grammatical and punctuation errors in your article. You may want to proofread it sometime or have someone do it for you and make the corrections. It’s pretty bad. Just sayin’

I would love to see where Possum fit in this test. I don’t believe they have pure possum. It is usually spun with other fibers.

This fiber has come up a few times. If I expand my fibers in a future test I will look into getting some opossum.

Opossums and possums are different animals. Possum fibres would be Australian.

I think something you could do as a control is have the same person spin all the fibres might help.

Being from the arctic I’m not sure I believe the results about qiviut. I wonder if you got a blend.

Thanks for the correction about possums. I wasn’t aware of this.

The Qiviut was certainly not a blend. Just by looking at it I can see all the fiber matches. I’m looking into other testing methods that might give different results.

We were in NZ once and a major invasive species there is Australian Brush-Tailed Possum. Hides are available, but the fiber itself is just too short to spin. It was being mixed with wool at a 40% possum/60% sheep ratio is my memory. Very soft, but has to be mixed. We didn’t come across ay straight unmixed fiber.

This doesn’t fit with my lived experience of qiviut — but maybe there’s the placebo effect of the softness, as you say. I can see a problem with your methodology, though, if I understand it correctly. Qiviut probably gets a lot if its insulation from its loft. If you place the beaker on top you are losing more loft perhaps than in some other fibres. You may need to support the beaker so it doesn’t squash the fibre.

Just looking at the fiber I didn’t see any reason that qiviut would be more susceptible to compression than other fibers. In fact some of the others seemed to compress more. That said, I agree that this is something that I should try to improve in my testing and I’ve been investigating if I can come up with a better testing apparatus.

I agree with this whole heartedly. From what I’ve read, it’s an extremely lightweight fiber (as is angora, but qiviut even moreso), much like down is extremely lightweight for the level of insulation. The only reason down insulates is because of the air pockets created. If you compress down, you end up with very little insulation. That’s why you aren’t supposed to store down long term in compression sacs and why you need to refluff thoroughly when they get taken out. Also why down does a miserable job of insulating when it’s wet. Angora and qiviut work in much the same way-the air trapped in between the fibers allows for extra insulation and when you compress those fibers down, you completely destroy that insulation.

I’d try actually wearing a pair of gloves or something made from each of these fibers in a controlled temperature environment for a similar period of time-maybe a walk in freezer? But really, if it keeps my freezing hands warm, it works. Ha.

Hi Maurice. This is great fun and very interesting. Another fiber sample that is pretty common and also has been rumored to be very warm is Mohair from Angora Goats. The old wives sayings are that it is also supposed to be warmer than wool. It is another fiber that has lots of “loft”. If you ever need some raw or spun mohair I would be happy to provide you with some.

Interesting! I have Siberian Huskies, I wonder how their undercoat compares to the Malamutes 🙂

Our experience is that there is quite a bit of variation from dog to dog, but generally a Malamute is fuzzier. Of course, in a cold climate they all get fluffier! Don’t waste that fiber. Regular brushing is best, since that doesn’t get the guard hairs. IF its too short too easily spin on its own,mix it with something that’s longer.

I am a sled dog musher. Have roughly 35 Alaskan Malamutes and/or Inuit dogs (close relative of the Malamute) is there a market for their fur for spinning? We live in Fairbanks Alaska so our dog’s coats are about as thick as they get. It would be col if their fur could help pay their massive feed bill. Lol

A comment on your testing method (also pointed out by someone else, I see):

“Then I put the insulator (a knitted test swatch) on the hot plate set to 120 degrees Celsius. Then I put the beaker of water on the insulator . . .”

The heat is transmitted by both conduction and convection. Placing the beaker directly on the fiber swatches will compress them, bringing the beaker closer to the heat source, thereby increasing conduction. I’d be curious about the results of running this experiment with the beaker held at a fixed height above the heat source at just the height of the idealized thickness of the swatch so there is no compression of the swatch.

But this does point out the problems in running these sorts of experiments, namely consistency and replication. Its hard to spin and knit two items that are identical in yarn weight, thickness, and tightness of knit or weave. Maybe do 10 swatches of each experimental treatment (in this case the type of fiber) and see how those results crunch out in some summary statistics. You might compare the weight of each swatch, as well.

My partner, Marianne, uses many different types of fibers, including dog, which was the first domesticated animal used on a regular basis for fiber. (The aboriginal peoples in the pacific northwest of north america had a distinct breed that was kept and used almost entirely for this purpose.) Softest of all the canid fibers my partner has used was from a Pomeranian. She’s also done a sweater with Samoyed, which glows iridescent white in the sun. But the nicest fiber of all (any type) was from a long haired blond dog that was an Akita-Husky (named Ganda). The fiber was beige-tan, long staple (4″-12″; undercoat up to 4″), completely waterproof (no absorption), lightweight and very fuzzy. My Ganda knit hat made from her fiber was very lightweight, completely waterproof, and incredibly warm (though the hat is now worn out after about 6 years). Our current packmate is a Malamusky named Takilma and my current hat is 40% Alpaca, 30% Malamusky, 20% Camel, and 10% Yak. Tight knit and very warm. Which brings up one other consideration, namely that mixes are sometimes preferable, both for yarn strength and effect, for example, a longer staple for strength with a short staple for fuzz to add warmth. Alpaca and Angora together would be an example. And Marianne just pointed out that a looser yarn and/or a looser knit will trap more air (up to a point) and thereby be more insulative. Think about the very thick but very loose Mohair sweaters popular in the 1950s and 60s.

Anyway, Marianne is counting the days until her Eel arrives. Keep spinning your wheels!

Thanks Steve for the great feedback. I’m actually working on a new test that tries to solve the compression issue (I still have no good feel for how much difference that causes for different fibers, but I do want to find out). My new test is basically putting a heated block of aluminum below the test swatches and seeing how long it takes to cool off. I did get some results from this, but the differences were very small. I suspect because too much of the heat from the plate is escaping by not going through the test swatch. I did insulate it, but apparently not well enough. I’m going to try some other ways of insulating around the aluminum block. If I can’t get this to work I might try your experiment suggestion, but I think not having anything to block air flow above the test swatch is better than what you suggested (at least it seems more like the case we are trying to simulate).

I agree a large sample of test swatches would be ideal, but honestly that is perhaps too much work for me. If I get a testing apparatus that I’m happy with I might be willing to lone it to others so they can do their own testing (or accept test swatches from others). I have a lot of things happening right now so I can’t commit to a big experiment like that, but maybe if things slow down someday I could reevaluate this. There are a ton of things I’d like to test related to yarn based on feedback I got from this. I plan to at least discuss some of these if/when I do an update for this project. That might in turn spark more ideas. I have added your suggestions to the list. Thanks for the feedback!

That (at least conceptually) seems to be a better approach, since it would then “measure” heat flow from both conduction and convection. Much closer to the “real world.”

If you can put together a good standardized experimental set up, getting people to submit test swatches might be a low work way to get the replication that’s needed for statistically robust results. The hard part is limiting the number of potential variables. If there’s more than 2 or 3 analysis gets way more complicated. A quick list that might not be too onerous to measure and track:

• size of swatch

• weight of swatch

• thickness of swatch

• fiber type(s)

Of course, replication, replication, replication!

Eric, would your partner make me a hat like that?

If so, drop me a line.

tony @ willingham . net

Your results don’t surprise me. I’m a very long time dog person and can tell you it doesn’t much matter what breed of dog you use as long as it’s the soft inner coat you are spinning. I would love to see the differences in something like an Afghan hound and the inner coat of double coated breeds. Sadly, I no longer have afghans so I can’t even give you yarn spun from them

Which breed of angora rabbit did you use for your sample?

Also would love to see where mohair (angora) goats rank!

It’s really odd about the results though. Placebo effect aside, when I hold qiviut as a fiber or as a knit object my hand gets hot to the point of sweating very quickly, not at all the same as various alpaca, or merino. And outside in -40 the qiviut hat or headwrap is the go to, vs any other hat, as there is a noticeable difference in trapped warmth around ears. Rabbit is a close second.

Could it be an extreme cold thing, or an exposure thing, I wonder?

Watch out, I’m going to be standing out in the cold in a month or so with a sensor on my head and sending results….

Another question:

Many times straight up qiviut or angora rabbit are thinner closer to lace weight. I wonder if thicker yarns of those fibers aren’t as effective?

Thanks for the feedback. I’m hoping to be able to do more testing in the future. Perhaps with more samples.

Sorry, I’m not sure what type of Angora rabbit fiber was used. My wife purchased the fiber many years ago at a fiber festival and it didn’t have any additional info about this with the fiber.

I agree with other comments regarding the issue of compressing the fibers under the beaker. Air pockets are one of the key insulating properties in many wools – not just the conductivity (or lack thereof) of the proteins which make up the fiber. It’s why double paned windows are better insulators than single pane.

In addition, you measured the thickness of the samples, but most warmth ratings are based on weight of fiber. Eg: if you are looking for the warmest clothing while backpacking, weight to warmth is the important ratio, as backpackers try to keep down the weight they are carrying. So a fluffy fiber may have the same thickness in the sample as a less fluffy fiber, but you have LESS of the fiber. You say all the samples have similar density, but only give the final thickness of the swatch. How much did each weigh? Did you have the same grams of fiber in each case between beaker and hot plate?

I agree with much of what you said, but it is an over simplification. There is a lot of tension based compression that happens with things like sweaters and scarves. Having some compression is a somewhat reasonable way to represent that and the weight of the beaker was light (I think it was just over 100g with the water in it) . However, I agree nothing is ideal here and I’m not really even sure how to make a perfect experiment without recreating real articles of clothing and either make complex heat models or use real people with several sensors. These kinds of experiments are beyond what I can reasonable do here. I’d be super interested though if someone could point me to such experiments. So instead I need to create simplified test jigs that hopefully do a decent job at measuring what we want. Since I made this post I did try making another test rig that had zero compression, but the data from that was terrible and showed very little difference between any of the fibers. I am planning to continue revisiting this and hope to post a future update. But right now I’m busy with some other higher priority projects.

I did weight the swatches, but due to the flexible, irregular shape, and non-uniform density I did not have a reasonable way to calculate actual densities and that is why I left out that information. Giving the weight without volume would be useless information at best or misleading information at worst.

I guess I should have read your comment here instead of posting mine, which is a repeat of Joanne’s.

Even without weighing the fibers, the test results are still very informative, a true contribution to the fiber arts. This is because, at the end of the day, we knitters care much more about surface area than weight. Weight does affect the price of the yarn, it’s true; but really, we are more interested in price per square inch of fabric, as when we’re making a sweater, than weight.

With this in mind, the beaker test is still very useful. the bottom of the cup is represents a uniform *surface area*, and as you point out, fibers get squashed all the time (under overcoats, under multiple layers, yarn spin, tension, etc.) and so it is important to see how they perform under those real-world conditions.

You point out that 100g isn’t a lot. I don’t think it’s tons, but it is something, about .98 newtons of force spread over the surface area of the bottom of the beaker. It would be interesting to know the surface area of the bottom of the beaker so that the pressure could be calculated. This would allow us to compare your experiment to the real world. For example, if I wear a hoodie (which might weigh ~1.5-3lbs, let’s say 1kg), its weight is chiefly resting on my shoulders. If I then have a Qiviut sweater underneath that hoodie, and my shoulder surface area is 10 times that of your beaker, then the pressure of your beaker would be the same as the pressure of my hoodie on the Qiviut fibers, yielding similar results of insulation on that part of the body.

The weight also seems to make the test more uniform in its results, though, so I can’t see how it could be done better.

It is interesting to point out that Qiviut fibers in their natural habitat *never* get squashed; they are on the underbelly. Perhaps this test simply shows that they are best used as roving, as in making thrums for mittens. That would be the best thing at respecting their monstrous price point anyways.

Thanks for the feedback. I don’t have the beaker with me right now, but I’d estimate it’s diameter is 35mm so from that you can do your calculations.

I tried to do a test where I put an block of aluminum in an insulated container and put the test swatches over it. My thoughts were better insulators would result in the block cooling off slower and there was zero weight on top of the fiber. However, this test didn’t work well. It turned out that most of the heat was not lost through the test swatches (evident by them all being very close). I’m still working on other methods of testing this and hope I’ll come up with another good one.

Fascinating results.

I wonder if maybe the results are reflective, not of just warmth, but of warmth *and* structure. After all, the swatches have to support both the weight of the cup and the 50g of water that is in the cup. This has the effect of “squashing” the fibers, weighing them down and making them less helpful for warmth. Hollow fibers like Qiviut and Alpaca are going to have a harder time holding up the weight, and the squashing might take out any advantage they had using hollow fibers. It may have the effect of cancelling out the “loft” of the fiber.

This might be why merino did so well: it has *tons* of structure, and was able to support the weight the best while still maintaining air pockets.

I’m unconvinced that alpaca and Qiviut are not warmer under other conditions, such as freely draping with room to expand, as in the side of a sweater. The results are very interesting and useful, however. Maybe this is why merino is preferred: it is *great* at the insulation/structure balance. Also, it shows that, even when Alpaca gets squashed, it still does a fantastic job.

Obviously the most interesting piece of trivia here is the performance of the Alaskan Malamute. I had a dog once that shed, maybe I should have kept the fibers.

I agree with your concerns here about my testing method, but as you concluded I think these tests are still interesting. I’m hoping that someday I can do some more tests to see if results are different when using different testing frameworks or different fiber samples. I believe Malamute fiber is hollow (correct me if this is wrong) and to my hands felt like it was as soft and collatable as any of the samples. That said I’d rather come up with tests that show this rather than having to rely on how things felt.

I absolutely agree with you point on loft. I live in Alaska and we love our qiviut. I’ve NEVER seen it knit into such a thick tight weave as used in this test. I believe (no proof whatsoever) that it needs that air space to provide such wonderful insulation.

Love the data based approach to answering this question!

I, like a few other people am very curious to see a similar test but without the “conduction” ambiguity that may or may not be caused by setting the beaker directly on top of the sample.

A modification that comes to mind would be for you to make an open bottomed box to sit on your hot-plate with the sample swatch somehow clamped in the middle to form two air-spaces. The lower air-space will be directly exposed to the hot-plate surface — and thus will heat up. The top air-space in the box will be insulated from the lower air-space by the swatch — so if you measure the temperature difference between the bottom air-space and the top air-space after they have sat a long time and reached equilibrium, that may be a very nice measurement of the insulation value against convective heat transfer.

There are many variables like gauge, stretching, etc…that would affect this rating, but if it’s a consistent test rig, you can simply open up the testing and ask people to submit swatches (I’d happily send a few)

This looks like a fantastic project!

Thanks for the suggestion. I actually tried a variation of what you described and couldn’t get reasonable test results from it. I’m probably going to try again someday. I will point out the one described wouldn’t actually work. That first air layer you described would be a far better insulator than any fiber. Basically with all these fibers they are trying to create the most airlike gap while stopping air currents. Your first air gap breaks the model we are trying to simulate. I think if we got rid of the first air gap then it would be pretty good in theory, but it breaks down because I can’t create a good enough insulated air space on top to reliably measure the differences. I feel like there must be something like this I could get working, but it probably requires better instruments or better built test harnesses than I’ve done so far.

Indeed, any approach sounds fiddly!

Thank you for the great information given. Do you know how cashmere would rank on your insulation results? (I’ve seen a website claiming cashmere is much warmer than merino wool.)

I didn’t do that test here, but I might revisit this and try to improve on the testing and add more fibers.

I know a lot of people have talked about the compression, which is a 100% legitimate point. But qiviut could very well be cooler than some other wool/furs. Musk oxen don’t rely on a high quality down alone to stay warm. They have very thick, dense coats for one. Heavier than many other animals and they’re much more compact than, say, alpacas, which are kinda lanky animals, and that structural difference itself will aid the musk oxen greatly in staying warm. They also have a unqiue ability to adjust their metabolism and heart rate to conserve energy. For another comparison, you could look at seal skins vs caribou skins. Caribou skins are used for winter wear, while sealskin is used for summer wear. You might think, with these seals living in arctic waters, they’d have to have a warmer skin. But its not a very good skin at all, for warmth. Because they don’t rely on their skin for insulation, but their blubber. Just because an animal lives in the arctic, doesn’t mean it’s going to have the very best down. Arctic animals have adapted in many ways to their harsh conditions. I wouldn’t personally be surprised at all if caribou down is warmer than qiviut, they’re not as compact animals and they don’t have as heavy coats, so its not unlikely that they would need a higher quality down. To be honest, the angora surprises me more. Being a small animal with little fat that can’t carry an egregiously large coat, it would seem they’d rely more heavily on their downy fur. But to be fair, these aren’t arctic hares. That you can tell at a glance, what with their gigantic ears. And I would hypothesize, being a rare luxury fur that’s never genuinely been used for survival, breeders of angora rabbits likely focus on softness and quantity over insulation, with the fur’s insulating properties simply taken for granted. I’ve really hardly ever seen any science comparing warmth factors of fur/wools, to be honest. Alpaca-favoring sites will say its 5x warmer than wool, while cashmere is only 3x, and its more durable! Hurray! and cashmere- favoring sites will says it is THE softest (uh, did we forget angora? qiviut?) and warmest wool of any natural fiber. The most logical and unbiased (not really scientific…) sites assume that finer always equals warmer. But it’s not. Hollow vs. solid hairs, kinky vs straight hair (and merino is very kinky! that will create a lot of air pockets!), these things are important factors. The whole qiviut thing reminds me of the blueberry antioxidant rage, with people saying, this berry has the most antioxidants of any food! But they don’t? Lingonberries, cranberries, bilberries, cocoa powder, coffee, almost all the spices and herbs, even raspberries have a higher orac value than commercial blueberries, which are the ones being touted. Obviously, for profit. Or like vitamin c for oranges, but again, they don’t? Bell peppers have way more. And potatoes are much better for potassium than bananas. That qiviut is the best seems widely assumed. I own some myself from my mother and am from Alaska and been able to interact with the animals, so I got a little pride in it. But this blog is the only site backing up its claims with any real evidence and not just making assumptions or regurgitated assumptions. I really appreciated that, and I don’t think we should be brushing off the results. Would love to see a follow up experiment! As for the softness factor, I know I 100% translate softness into warmth. And a lot of the time, when using fur or wools, they’re all insulating enough that it doesn’t really make a big difference which you use. Layering is much more important than having THE warmest wool. Or good fabric/yarn construction, for that matter. But oooh, the cozy factor of those soft, luscious furs~ I love angora blends and cashmere~

This is one of my favorite replies to this blog post. Thanks! I really like how you think through different animal physical features. While I don’t think that proves anything it is certainly worth thinking about. I also like how you point out different sites have different claims that align with their biases.

I would like to do a follow up experiment, but the ones I tried didn’t work out that well. I hope to have a better follow up someday. Maybe I can find a university that has better testing equipment or something to assist.

I recommend (only read thru this post here – sorry!) that you reach out to the Weavers Guild of Minnesota –

https://www.weaversguildmn.org/

I am in NYS but I watched a livestreamed spinning and weaving seminar they offered during the COVID lockdown – it was all about spinning and weaving with wolf fur. The woman presenting was VERY knowledgeable and absolutely delightful. I am sure if you contact the guild, they will connect you with her. I actually tried to record the podcast, it was so wonderful. Good luck and keep working on this – it is unique and really valuable information.

I read that Arctic fox is the warmest fur. Here’s an example of a blended yarn I saw:

https://aurorayarnsofalaska.com/product-category/arctic-fox-hare-yarns/arctic-fox-yarn/

It’d be nice if it was more substantially Arctic fox, but it’d still be interesting to see how it compares.

Also, caribou would be interesting , as it’s been used for its warmth, as well as sea otter, being the most dense fur.

It’d be interesting to see how pelts with the full coat in its natural state measure up to yarn, as well as if felt vs yarn makes much of a difference.

As well, it’d be interesting to see how different types of down compare.

A u-value measurement would be nice for more standardized comparison.

I’m not sure this is a valid test. I saw compression notes but under this sort of testing, concrete would be better than any of these animal fibers, and as most people know, concrete is a lousy insulator. The ability to retain heat may not have a direct correlation with the ability to stop thermal transfer. Related but unrelated. Use cotton as a control.

I once saw a skein of Marmaluke spun yarn. The spinner told me that the great advantage was that if you knitted it into a balaklava for instance, the water vapour from your berath would not freeze on the spun fibre.

drew barrymore

1 second ago

Great effort and admire your attempt,

However your methodology about testing fabrics is incorrect, also, your own interpretation about what makes a yarn warm in your understanding of insulation is also wrong. By definition insulation ONLY refers to how a fabric allows heat to passage, but this is only 1/3 the equation, this is because you should ALSO measure how fibers deal with COLD in the OPPOSITE direction. Last your mythology doesn’t include with something called wicking, the other 1/3 of the equation, if you are using the hot plate as an example of the human body’s temperate as it gets covered with a chosen fabric, then you should understand the human body perspires air molecules and this changes completely the insulation properties of any fabric called humidity. As warm as you might think some yarns might be as soon as as water reaches the fabric it becomes saturated by it, as a result the warmth properties automatically collapse, this is called water saturation, a clear example of this are regular merino wools, they definitely warm, but in the luxury world they aren’t considered great insulators, after you wear merino for a few hours the fabric starts to feel damp this is a clear signal of lost warmth and saturation of water and makes a savvy wearer feel yucky unpleasant, in comparison yak wool which has the highest amount of saturation of almost any fabric by 40% you can wear yak wool and will feel toasty warm & dry for hours, another clear misinterpretation is the result of silk in your controlled experiment, though it might be based in numbers for some minutes or hours, it isn’t true in the real world, silk not only collapses fastest than any fabric on its wicking properties, it also begins by disintegrating loosing all of its properties faster than any fabric, this is the reason why even the best of silks needs to be replaced constantly in the finest of lining suits and coats in the tailor industry, you might think silk is warm but trying wearing silk in the coldest of temperatures and you’ll rapidly regret it, this is because you have not tried to conceived the cold factor in your understanding of what makes a yarn warm, it isn’t just real insulation by ALSO admitting WICKING factors, but how a fabric deals with the COLD. You could leave all your swatch fabrics out in the cold and then feel them to test how deal with cold, as far as I know Muskox feels and maintains a warm feel to it on the outer side in 10 Degree windy weather which is crazy, it doesn’t seem to be affected by the cold.

Last I will suggest you read about Vicuna, this is because muskox is as fine in micron count as vicuna and when you go that small you begin to understand that those fabrics (which I own both) trap the molecules of air between its fabric, that is what makes those fabrics so magical and warmth, is how they deal with the release of hot air molecules trapped between the fiber blocking incoming cold air and pushing out new hot air released by your body, this process is what makes those fabrics FEEL luxurious, we can all wear 2 layers sweaters, a vest, a jacket and a coat, but it’s unpractical and you’ll definitely FEEL uncomfortable, that is why some commercial non high-end cashmere sweater’s feel unpleasant and why people automatically assume that all cashmere is/FEELS the same, not until you try the highest grade of cashmere in the market you’ll begin to understand the various FACTORS that go into deciding what does it MEAN by WARM in the luxury market.

I admired your attempt,

Cheers

I keep seeing this concept of heat transfer and cold transfer being different. It is not for these standard insulators. They block heat transfer equally in both directions. There are really exotic substances made in the lab that do only transfer heat in one direction, but those are relatively recent breakthroughs (1970s). Here is a short article that talked about one of these substances: https://www.popsci.com/science/article/2010-03/new-polymer-conducts-better-metals-only-one-direction/

I’m not as sure about the rest of your claims so I won’t comment on those. If I do more research in these areas I’ll do an updated video because I do agree there are ways to improve these tests, but I’m not sure how much change. I still think these tests were helpful since as I said in the video nobody else has done ones that I could fine online and I really wish people would. Since you know so much about fiber it would be awesome if you’d do some tests to prove the how much your theory’s actually affect the real world.

Your assumptions about silk’s ability to insulate are wrong. Though I agree that heat transfer is only part of the equation (the cold transfer part makes no sense, unless, as Maurice said, your discussing some exotic lab product). Wicking ability IS incredibly important. This is why people say cotton kills. It gets damp from sweat when you workout and overheat, it loses all its insulating value when wet, takes forever to dry out, and its like wearing a damp towel at 20 below. I still wear cotton jeans in the winter, but I wouldn’t dress like that if I were going on a winter expedition. But you only need your base-layer to be wicking, anyway. Take a down jacket for instance. The last thing you want is wet down. Its worse than wet cotton. So down in jackets is invariably encapsulated by some water-resistant/proof synthetic material. They are not moisture-wicking. Yet a GOOD, heavy-duty, down jacket is the warmest jacket you’ll ever wear. No one wears down as a base-layer. Some people call their down mid-layer their “base-layer,” but then you see they’re actually wearing, like, I don’t know…a cotton shirt under that.

Back to silk. You will see some sites claim that silk is breathable, moisture-wicking, and odor resistant, and is therefore great for hot weather. I don’t believe a lick of it. Of all the “summer ” natural fibers I’ve ever worn, it is the most stuffy and hot, it shows sweat stains like nobodies business, and it reeks like polyester. The only thing I like about it in hot weather is that it is super light and thin. So I think you’re right in saying its moisture-wicking ability sucks. Silk is hydrophobic though, like wool and unlike cotton, and is noted for drying quickly (but I’d postulate that’s just because its always woven so thin). Regardless, I love silk on chilly summer days: because it is insulating. In “Physical Properties of Textiles Fibres by J.W.S. Hearle and W.E. Morton,” they compare the thermal conductivity of pad fibers with a bulk density of 0.5 g/cubic cm. The higher the number, the more thermally conductive, and thus the less thermally insulating the fiber. (Units are in mW/mK & Air = 25) Nylon = 250, Polyester = 140, Cotton = 71, Wool = 54, and Silk = 50. Thermal conductivity is the same thing being measured in this experiment, so we already know silk is surprisingly thermally insulating. You’re saying that’s not all there is, that’s true, but using a warm or cool “touch” isn’t exactly scientific. It can be helpful, but it indicates a variety of things. A cool touch can indicate a smooth substance (more surface area for heat transfer to occur), a thermally conductive substance (heat transfer occurs faster), a substance with high heat capacity (it takes more heat to warm it up). Silk has a heat capacity similar to wool, you can reference the same work I mentioned earlier to see that or other studies. A high heat capacity is indicative of a good insulator. Why? Because a substance that has become warm from being heated is now releasing its excess heat – that’s why you feel it. But you want to retain as much heat as possible. Why then does the qiviut have a warm touch if it has a high heat capacity? In this case, because it is not thermally conductive. On the other hand, silk typically has a cool touch to me. Yet its thermal conductivity and heat capacity is similar to wools. How is this? Because it is extremely smooth. Silk sheets are like a trap to me. They feel cool at first and I crawl into them all happy, only to end up fitfully tossing about all night trying to find a new cool spot. Despite the initial “touch,” they are not actually a good cooling substance but a good insulating one.

Now, I wouldn’t want silk as a base-layer, since its seems poor at wicking (to me, at least) and smells. But it would make a great mid-layer and a pretty snazzy outer-layer. The caveat? No one makes thick silk garments. No one. Never seen it. Silk isn’t about insulation. It’s about luster, drape, and that incomparable luscious feel. It’s about being the lightest, strongest fiber. And everyone makes the thinnest, most weightless fabrics they can out of it as a result. Nothing that thin is going to keep you warm unless you layer, like, 30 of ’em (or have a long shelf-life).

I would be interested at how Vicuna would have placed in your test.

Tom Manning, a taxonomist who spent a great deal of time in the eastern Arctic, told me once that overheating was a more serious problem in the north than cold. He was speaking of humans, of course, but I wonder if quivuit undercoat adaptation is more complicated than just insulation.

The domestication of sheep over thousands of years has resulted in fibers which are far from adaptive – except to meet human needs. I wonder if that might provide part of an explanation for the surprising results.

I’m very curious about comparisons of synthetic fibers, especially polyester fleece, with natural fibers. There are emerging environmental concerns about the toxicity of fleece, which is unstable. You mentioned that you were unable to obtain acrylic fiber to sample acrylic. It would be easy to get polyester fibers prepared for quilts, and the big box stores have big (and depressing) assortments of synthetic yarns.

Thanks for sharing your experiment, and your patient and careful responses to comments. You’ve generated a wonderful discussion.

I am a cold weather camper and have been working on improving my setup each year. I can’t quite find socks that work great in subzero at night when circulation slows down, so I am thinking about making my own. It is nice to see that “normal” wools should work fine. Compression may be an issue with your result, but then you haven’t accounted for wind either. But then each of these matters in different circumstances. A complete (not better but more complete) test may look like

1) Compression test (as performed in this blog)

2) No compression, no wind – radiant heat lamp with a glass of water inside a swatch (basically make a cozy for the beaker)

3) No compression, with wind – repeat 2 but this time have a small fan circulating air

I think that would give you a good setup (socks & tight clothes with compression), windless cold, windy cold. You may have different fibers performing at different levels.

Separately, I’d love to see how yak performs.

I wish I could figure out what the ” magic” is of a blanket I bought in Mexico. I ” think” it is handspun cotton but not sure. It is warmer by miles than any blanket I’ve ever owned and has an amazing capacity to trap body heat and keep me toasty warm on even the coldest nights even though it is loosely woven. I use it right against my skin. I bought it from an elderly woman on the beach and I have a feeling it was handmade. No blanket comes close to it’s insulating capabilities, not even the other Mexican blankets I bought while there that look similar but not exact. Any thoughts? I’ve used this one so much that it’s starting to break down a little. I’ve always called it my magical ” Linus blanket” and had I known how soft and warm it would be, I would have bought ten!!!

Fascinating article and excellent topic and research! I am a weaver, spinner, and research statistician, and I should know. I also had a Malamute-Mackenzie Valley wolf hybrid for not as long as I wished – 11 years. He used to lean/lay on me, on the bed, on/in a sleeping bag, in the truck, on a chair, on the floor – anywhere he could find me. And I can testify that he was a mobile furnace. I wish I had collected his undercoat over the years. Now I know better. Thanks a lot for this great article!

Hi, this was a very interesting article and discussion below. I am wondering if you have done other experiments. I am actually researching specifically for heat transfer. I would like to make one of those insulated cooking bags, I think Wonderbag was the company that pioneered the design.

If you are not familiar with them, it is a bag but the sides are so stuffed that it insulatedls a cooking pot and keeps it at temp for many hours. You bring the food up to the right temperature and it will continue cooking in the bag all day, depending on the size of the bag and the pot, the smaller ones do not last as long. Can be used to make yogourt as well, but I think this didn’t work out as well for me. I cannot recall. Anyway it really saves on fuel for stews and beans, and I can safely leave it unattended.

Unfortunately they are no longer for sale in the US (at least the size I want) and I did find a pattern online. Wonderbag used some synthetic filler, so I thought if I am making my own why not a natural fiber. Thus, I am searching for the warmest possible fiber to make it really worth my while and last as long as possible. It requires a sizeable amount of wool to stuff one of these. Wondering if I can contact a dog grooming business and see about getting ahold of malamute fur 😁

I am interested in doing my own experiment, making a couple and just trying them out with the same dish in the same pot, but given the quantity I need and some of these fibers are pricey I kind of want to narrow down to a few best options. Curious if you have any thoughts from your experiments! I already have a lot of Jacob wool so that will probably be one of the options.

That is really interesting. I want to do more experiments in this area some day, but have been too busy with other projects. I don’t think I have much to add to your idea, but if it’s not too much work to do then I’d probably start with just a low cost fiber for the first version and see how it goes. You’ll probably get ideas while making it and be able to do a better job on the second one.

I have a sled dog kennel here in Fairbanks Alaska with around 35 Malamutes. I just inquired above about whether or not there’s a market for the fur. I sure wouldn’t mind turning their fur into money to offset feed costs

Thank you so much for this study genius!

Here are 2 links to Facebook photo albums of Malamute undercoat hair that I spun and knit for a friend of mine. I love dog hair more than any other fiber that I’ve tried because I’ve tried all the ones that are mentioned in your test, except for paper towel! All dog breeds in the Spitz family (Samoyed, Keeshond, Newfoundland, Malamute, Akita, Pomeranian, Eurasian, …) have the softest and warmest undercoat . What I like the most about dog hair : it is 1- free, (no chemicals added for scouring, dying, straightening, mordanting, machine processing and making it Super Wash); 2- all natural and biodegradable thus non-polluting ; 3- local ; 4- best of all, it is sentimental for the dog owner.

https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.2185202838287974&type=3 https://www.facebook.com/share/p/19XzN72bAN/